Change is the norm now: new companies, new teammates, new roles every couple of years. To be effective at our software engineering jobs, we have to be comfortable learning new systems and processes quickly, but we also need to learn to leave positions gracefully. The last thing we want as software engineers is for our hard work to be for naught because the people picking up where we left off can’t decode our code. It’s up to us to work out loud: to document and share our logic and thinking to ensure a smooth transition when we’re gone.

This is especially true for Commit engineers. Commit’s model is to connect engineers with startups, offering opportunities for both groups to know each other and work together before either commits to a long-term opportunity. By its very nature, this creates many transitions in and out of organizations. As I’ve progressed in my career, working with many different teams and startups, I’ve given thought to how best to pass the baton to the team members I’m leaving behind, so there is no loss of knowledge when I go. Here are the ways I work to ensure a seamless transition when I’m gone.

Documentation

Believe it or not, it starts with your on-boarding. When I start at a new position, I like to “work out loud,” to document what I’m doing and why, right from the get-go. I set up folders in the organization’s tool of choice (for example, Confluence or Notion) and start writing RFC documentation for the high-level components I’m designing, whether it’s front end, back end, DevOps, etc. I also like to map out data flow diagrams to visualize the systems we’re planning and building as it makes it easier to build a mental map when talking about the systems with colleagues.

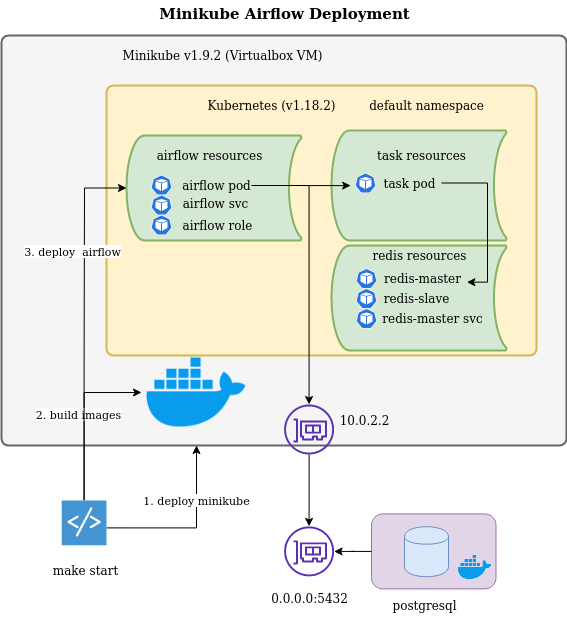

Dataflow diagram included in RFC documentation and linked to the repository README.md

From here I link my design/POC tickets back to these documentations. The key is to document what I’m thinking and the logic behind my decisions, so that when I leave, someone can step in and continue the work with little or no time getting up to speed.

Roughly two weeks before the end of a fixed-term contract, I’ll review the documentation I have in place and formalize what’s there. But I strategically leave gaps in it. Then I meet with team members to discuss the hand-off process and have them review the documentation and fill in the gaps. This is a way for them to get their hands on the work, instead of just reading about it, and to gauge their understanding of the components. If they can fill in the gaps, great, they clearly understand the processes. If not, it’s an indication that we need to sit down and discuss it in more detail.

Tooling

Another way to help smooth the process of exiting from an organization is to use tooling to automate processes. It’s almost like you’re still getting work done, but you’re not there to do it.

When my time in a particular position is coming to an end, I review the internal tools I’ve helped configure and write shell scripts to automate as many processes as possible. Examples include packaging CLI tools such as kafkacat, AWS CLI and Octant into a Docker container, so it’s easy for others to start using them without having to deal with installation for Windows, OSX or Linux environments. In addition, I make non-sparing use of Makefiles and shell scripts to encapsulate steps like introspecting a cluster, deploying a local dev environment, and setting up a database.

Training

The third approach to setting a company up for success when you’re on your way out is to train the people who will take over from you. This is especially relevant for complex processes and systems, where documentation and tooling provide a great start, but more direct knowledge-sharing is necessary.

On one of my recent contracts, we introduced Kubernetes, known to be a rather complex, heavyweight application. Soon after we got it running, my contract was coming to an end. We had set up documentation describing the processes and practices involved, and automated as many processes as possible through tooling, but we realized that direct training would be needed to ensure the organization would be up to speed on operating the system. We held two four-hour training sessions, introducing the entire 25-member engineering team to Kubernetes, including hands-on sections on how to perform end-to-end deployments and operate the system using the tooling we created to deploy applications and perform rollbacks and disaster recovery.

Build bridges that last

Of course, leaving a position or a company isn’t just about preserving the knowledge you’ve gained and the processes you’ve helped build. The relationships I’ve built are usually the most meaningful part of every job I’ve had: the people I’ve met, the communities I’ve been part of. Preserving those relationships is important to me, not as a career-development strategy (though that’s admittedly relevant), but simply because these personal connections are what makes the work worth doing.

There are ways to keep your friendships and professional relationships strong even if you stop working with people. You can join Slack channels and other communication networks, you can set up monthly Zoom calls or social events. One thing I like to do is write LinkedIn recommendations for my colleagues. It’s a perfect pairing of professional promotion and personal positivity that proves productive for all parties.

And it’s just a nice thing to do.

Do you have tips for leaving a role in great shape when you leave? Let me know in the comments below!